ABOUT THE PROJECT

Introduction

The project of this website was created for an undergraduate advanced French history and culture course entitled Paris under the German Occupation and its [Non-] Places of Memory. The French title is a play on the words « lieu de mémoire » (place of memory) and « un non-lieu » (a dismissed case). The first questions I was faced with when putting the syllabus together were: How could students of French, from an American university, understand a past neither of us lived? And how to expect students – some of whom have never been to Paris - to envision the city under the German Occupation without even knowing its space?

After piloting the course and getting students’ input at the end of the semester, the idea to create an interactive map came as a way to address these questions. The Authorial London Project was a first source of inspiration. Unfortunately, it was a Stanford developed software which was not ready to be shared yet. So with the support of the Penn Libraries and the Price Lab for Digital Humanities, a first map was designed using the plug-in Neatline and hosted on the open-source web-authoring tool Omeka. Later, in the summer of 2021, a Price Lab cohort started the creation of the current website. The bookshelf design, inspired by the Otlet’s Shelf Tumblr theme encourages viewers to “browse the shelves” and provides a space where the stories of individuals who vanished recovered their voices.

But before going into the story of the creation of the map, let’s take a detour…

Detour

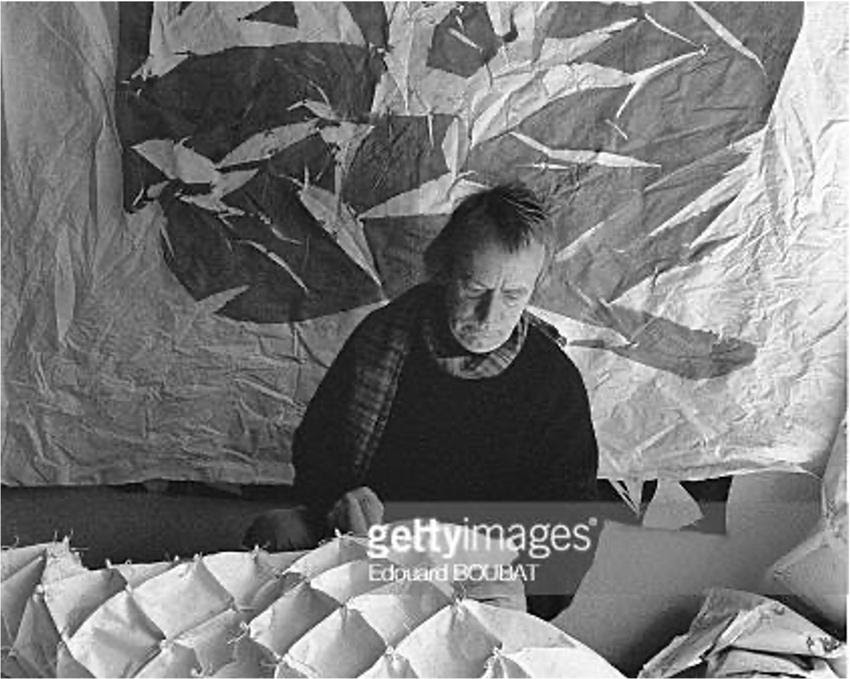

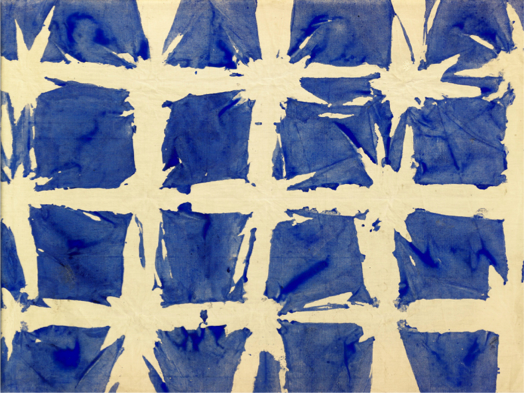

The painter Simon Hantaï developed a particular method he called folding (pliage). The word method versus the word technique highlights the fact the painter did not claim full control over the means he employed and did not aim at a definite outcome. His method consisted in folding, creasing, knotting the canvas whose dimensions were usually excessively large.

He then proceeded to lay the canvas on the floor and painted its visible convex spaces. Being on his knees and bent over his work, Hantaï intentionally denied himself full sight and could not foresee the final result. This is what he called “retinal silence”. Once the paint was dry, he proceeded to unknot and unfold the cloth.

In the catalogue of a 1976 retrospective, Hantaï shared a picture pointing at the origin of his method. The picture shows his mother wearing a meticulously ironed apron. The symmetrical creases visible on the shiny cloth turn the maternal apron into one of the canvas painted by the son. Therefore, one can say his folding method helped the painter bring back memories to the surface.

The unfolding acted as a revelation. Hantaï talked about chance (hasard) as a key agent in his work for conjuring up what he could not even imagine or think of. Georges Didi-Huberman poetically calls étoilement the white starring effect left at the intersections and created by the knots. The poet Dominique Fourcade explains that the starring effect represents “a sort of lifting, suspension, a prolongation of a time that is not supposed to last.”

When the canvas is stretched and finds the verticality it was denied while in the making, one can find themselves hear and see its heart beating.

“I realized what my true subject was – the resurgence of the ground underneath my painting.”

Let’s go to the map…

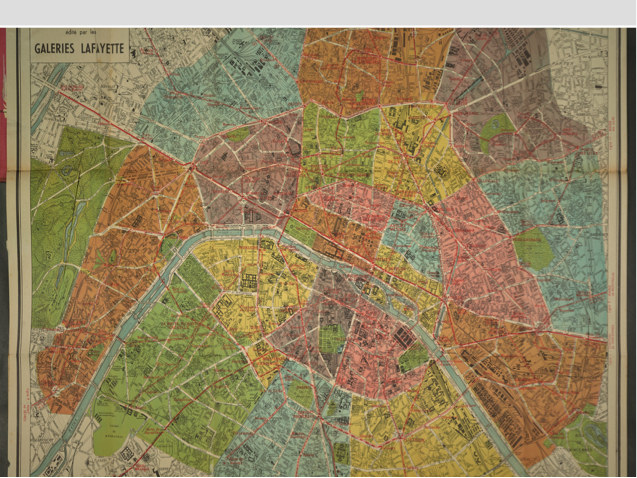

Part I — Mapping as Method

First, for 5 euros on eBay, I bought a promotional 1940 pocket agenda book with a map of Paris folded inside. It was offered to the customers of the famous department store Les Galeries Lafayette. I liked the idea of a map that had been carried around and manipulated by a stranger instead of a sterile reproduction. Besides, the story of the department store itself is a page ripped out of the history of the German occupation. By the end of 1940, it was aryanized meaning that its Jewish owners and employees were evicted and replaced by non-Jews. The map was unfolded and scanned with the creases time had left in its fabric visible.

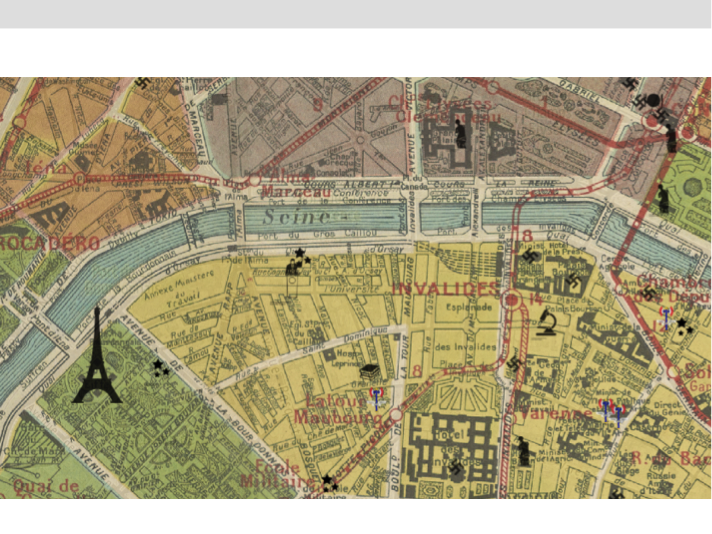

The digital image of the map was then layered onto a digital map of current Paris and the vintage paper map refolded back in its pocketbook. From then on, I followed the same method rooted in unpredictability as Hantaï: bent over the canvas my floor strewn with books, lose sheets, notes, had become, I adopted the dislocated, floating vision of Hantaï. I selected material in accordance with the goals I had for my class specifically which was to make the time period as palpable as possible. I knotted texts together, images and texts together. Instead of brushing paint over this montage as he did, I translated it onto the map using the Neatline platform. Despite the frontal position I suddenly had facing the screen of my computer, I still proceeded blindly. Mechanically pinning, stitching onto the fabric of the map never knowing what was going to appear in the end and if there was even an end. When I would zoom out, blanks punctuated the map. Yet, surprisingly, they were not obscure blanks, signs of an inevitable erasure. They stood like semaphores that led me to keep on looking.

About 240 key places were geolocated and identified with a description of the place before the war, during the war, and after the war. The places were first selected following Cécile Desprairies’s invaluable guide Paris dans la Collaboration which is organized by arrondissement. Almost each pin comes with a picture and with excerpts

• from selected memoirs written by key actors who survived and were published after the war e.g. the prefect of Paris Roger Langeron, the journalist Pierre Audiat, the lawyer Maurice Garçon, the novelist Jean Guéhenno, the historian Georges Wellers, the German artist Arno Breker

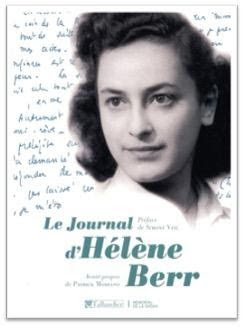

• from the texts written by 2 young key witnesses who did not survive the war: Hélène Berr, Louise Jacobson

• from the writings of young witnesses later turned writers: Sarah Kofman, Marcel Cohen, Patrick Modiano, Georges Perec

The map’s significance lies in the spatial visualization of history it provides and which contributes to reducing the historical and psychological distance that separates us from then and them. We can take the example of the Vélodrome d’Hiver where 13,000 Jews were locked in after being rounded up on July 16th, 1942 and before being sent to concentration camps.The velodrome was an indoor stadium famous for its bicycle races. In the mid 30s, it hosted many political conventions led by the future Socialist prime minister, Léon Blum, a Jewish man. The July 1942 round-up is known today by the name Vel d’Hiv round-up. Being able to see where the Vél d’Hiv stood – it does not exist anymore - first makes us realize how shockingly close it was from the Eiffel Tower (in fact, it was a short 10 minute walk). We can also read from the map that it stood amid the liminal space connecting the industrial neighborhoods in the south – best represented by the Citroen car factory where Taylorism was first experimented in France - and the area developed through the various world fairs Paris hosted. One of the characteristics of those fairs was to build places programmed to be erased from the map almost immediately afterwards and replaced soon after.

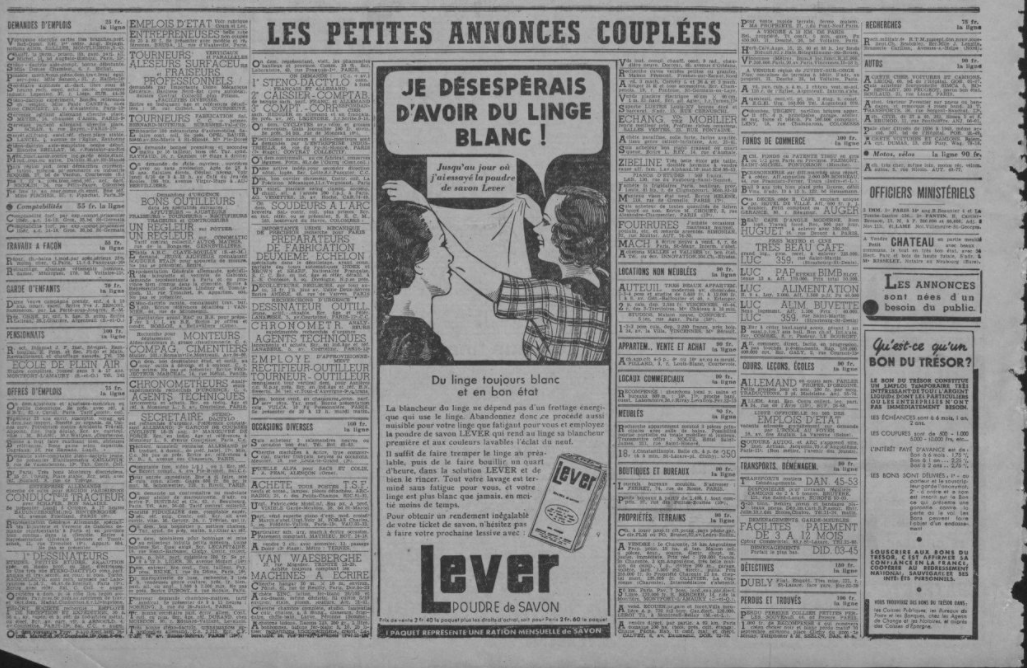

Clicking on the Velodrome pin on the map gives access to pages from period newspapers which in turn give the reader closer access to the fabric / fabrications of the time. In fact, in the newspaper from October 1941, three sections are referring to the Vélodrome : Nélaton and Grenelle which are the names of the 2 streets the velodrome was located at and then under the title “La Nuit des Etoiles” (The night of the stars) which fortunately does not refer to the yellow stars that were to be worn the following May.

Besides the obvious reminders of the historical context such as the ads looking for employees who could speak German or the mention of coupons to buy daily life necessities, if you take a look at the cartoon and the ad for the laundry detergent, you see insidious forms the ideological narrative of the Vichy régime took. They echo the pervasive rhetoric on cleaning / cleansing the social fabric which took its most dramatic onomastic form in the code name given to the July round-up: Operation spring breeze. On the page with an article on Cerdan, we read that only 2 short months after the round-up, the Vel d’Hiv was back to its entertaining function: it hosted a boxing match with the most famous French boxer Marcel Cerdan. The proceeds were to be donated to the families of prisoners in need. If the fundraising event tries to cover the antisemitic crimes commonly committed at the time, the announcement for a large public auction, right beneath, “brings back to the surface the ground underneath the paper.” In fact, the announcement echoes the flourishing public sales of spoiled Jewish properties. In the context of the map, it encourages to click on the icon for auction houses and leads the reader to understand the intrinsic connection between the commercial activity of the place and the cleansing ideology put in place by the Nazi and the Vichy regime.

So combined with the various material highlighting, on the one hand, the transitory nature of the space and, on the other hand, the pervasive theme of sanitation, the visualization of the location of the velodrome seems to tell us the story of a building predestined long before July 1942 to serve the role of antechamber to the gas chambers and which predicted the amnesia surrounding it after the war.

The story of the Levitan building shares similar characteristics. Located near the Gare de l’Est which is the train station to eastern destinations, Lévitan was a famous modern furniture store owned by Mr Levitan, a Jewish man, who was known for his innovative marketing campaigns in the 1930’s. On one of those ads shown on the map, he is presented as a perpetual member of the railroad workers brotherhood and offers special discounts to his so-called brothers.

On another one, a blond child thanks him for offering her toys while another ad promises that the Lévitan furniture procures family bliss and forever youth. In 1943, as Hélène Berr writes in her journal, it was turned into a warehouse where captive half-Jews cleaned, fixed and packed looted Jewish properties such as toys, living-room sets, linens to be sent to Germany for families in need. It also became the personal department store of occupying Nazi authorities who regularly came to shop for free. The remaining stolen properties left by trains from Gare de l’Est heading to Germany where many presumably blond children were happy to play with same as new second-hand toys. By trains from Gare de l’Est so did convoys of Jews leave heading to extermination camps. Many were unfortunately forever young. The building is today the headquarter of Le Bon Coin the French equivalent of Craigslist.

While famous Parisian locations are already known to most students, the map summons the untold narratives hidden behind these places. It reminds us of what Patrick Modiano, who received the Nobel prize for “the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world of the Occupation,” described in his Oslo speech:

[...] in my youth, to help me write, I tried to find the old Parisian telephone directories, especially the ones that listed names by street with building numbers. I had the feeling as I turned the pages that I was looking at an X ray of the city – a submerged city like Atlantis – and breathing in the scent of time.

Neatline makes the ontological connections between the temporal layers literally visible, further supporting Modiano’s palimpsest metaphor. As a matter of fact, upon logging into the map, for not even a second, one can witness the layers overlap, the WWII map coming together and eventually laying over the current map of Paris.

Part II - The Revealing of the Interstitial Whites

The background of the course was initially woven around the stories of three young women: Hélène Berr, Dora Bruder and Louise Jacobson. Hélène wrote a diary started in 1942 and interrupted in 1944 when she was arrested. Louise wrote letters written during her captivity in the Drancy camp. Dora’s parents wrote an ad in the newspaper asking for anyone who saw their runaway daughter to contact them. They all died in deportation.

"I can’t hear what she says." The lexical confusion of a student whose mother tongue is Spanish was another seminal moment. Translating entender (to understand) by the French entendre (to hear) to explain that she did not understand what Hélène Berr wrote actually made sense: how to understand History if you cannot hear the stories of those who were directly impacted by it? How to connect with a time if you cannot relate to the people who lived then? What about the stories of those who did not write the history books? Those whose voices were not heard either because they were not considered as major sources or simply because they could not talk anymore?

Starring Effect 1

I was granted the Rutman Teaching Fellowship to conduct research at the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive. The VHA counts 52,000 testimonies from Holocaust witnesses. About 2,000 are in French. I had only 4 days. In order to find my way amidst this ocean of stories, I searched the database using the keywords Dora, Hélène, Louise, the location Paris and each girl’s year of birth as cross-reference criteria. I was looking for women who, unlike Dora, Hélène and Louise, were able to physically tell their stories, after the war was over. This is how I met Francine Christophe, Annette Muller and Arlette Testyler.The narratives from the Shoah Foundation VHA literally help the students hear the past and the voices of those who vanished or were not expected to be heard. The testimonies were transcribed to facilitate the comprehension and individual maps were created to host these voices. In this case, the digital maps enable us to follow the witnesses’ steps through what was once their childhood landscape.

Starring Effect 2

A new question emerged. Now that we could hear the voices of people, what about hearing the city itself tell the stories? After all, I might have misunderstood my students’ sentence: "I can’t hear what she says." The pronoun she could have referred to “the city” which is a feminine noun in French. I can’t hear what the city is saying. So how to make the city talk?

Inspired by the Penn conference entitled Immersive Storytelling: Creating Narratives with Virtual and Augmented Reality in April 2019, and more particularly by Peter Decherney’s work using 360-cameras, I thought it would be interesting to film in 360 the places mentioned in the survivors’ testimonies as they stand today. In the Summer of 2019, Rachel Jedinak (née Psankiewicz) was filmed where her family home once stood, in front of her elementary school and walking to the Bellevilloise where she was locked in with her mother and her sister on July 16th 1942 after they were rounded up. Since Annette Muller was too ill at the time, her oldest brother Henri was filmed in the same neighborhood as Rachel Jedinak and heading to the same ominous place, la Bellevilloise. Both were able to escape on July 1942 unlike their respective mother and Annette who were taken to the Vélodrome d’Hiver later on that day.

Back in the classroom, when watching the videos with the Oculus headset, the students find themselves walking next to Henri and Rachel. In this instance, VR enable the digital cartographic translation to don a humanity that speaks to us in a way that we can hear today. The first time I watched the Bellevilloise video with the Oculus headset, I realized we were walking past a small thaï restaurant. On its bright yellow front, one can read its name: L’Echappée which not only means “the escape” but is also a cycling term which means “the breakaway” -it is common for cafés in working-class neighborhoods to bear names in connection with popular sports such as soccer or cycling- as if the street itself was telling the story of Rachel and Henri who, because they did break away from the Bellevilloise were not taken to the velodrome. A name on the façade turned the street into a Greek chorus and turned a restaurant into a textual mise-en-abyme. Interestingly, after the Vélodrome d’Hiver was knocked down in 1959, none of the nearby hospitality establishments that existed when the velodrome was still around kept names referring to the stadium. The physical erasure of the building triggered a surrounding amnesia.

Despite the pandemic, Francine Christophe was filmed in 360 in the Fall of 2020. We are hoping to be able to film Arlette Testyler next.

Conclusion

The website opens an interstice into the fabric of time and space which enables us to connect with a distant past and a faraway place. Recalling the very mechanism of breathing, the back and forth movement between past and present, historical narratives and individual testimonies, here and there keeps the blanks from becoming obscure and hollow. It encourages the viewers to not only consider the time period but also to be considerate towards those who lived it. It enables them to feel empathy towards people and a time they could not hear at first. The present endeavors put on the map the unheard stories of invisible strangers, stitched together scattered narratives, and weaved an infinite constellation connecting that past to our current present.

"Today, I get the sense that memory is much less sure of itself, engaged as it is in a constant struggle against amnesia and oblivion. This layer, this mass of oblivion that obscures everything, means we can only pick up fragments of the past, disconnected traces, fleeting and almost ungraspable human destinies. Yet it has to be the vocation of the novelist, when faced with this large blank page of oblivion, to make a few faded words visible again, like lost icebergs adrift on the surface of the ocean" (Modiano, 2014)

All the participants to the website might not fit the definition of novelists but were nonetheless all at once close readers, translators, cartographers, videographers, curators, who “realized what [their] true subject was – the resurgence of the ground underneath [the] painting.”

Sources

Georges Didi-Huberman, L’étoilement – conversation avec Hantaï. Editions de Minuit.

Dominique Fourcade, Simon Hantaï – catalogue de l’exposition. Éditions du Centre Pompidou.